For speed demons that can hit 250 miles per hour, Formula 1 (F1) design shifts are glacial. As author of Red Bull Racing Matt Youson wrote, “F1 is a sport of evolution, rather than revolution, with an annual nip and tuck to improve safety, cut costs or seal loopholes. Genuine change is rare – but when it comes, it tends to be epoch-defining, marking the end of an era or the start of a dynasty. In that context, the changes wrought at the start of 2022 are immense: quite possibly the most ambitious transformation in the history of the sport, certainly the biggest in the last four decades. It’s a new era of F1.” Even F1 tourists can spot the dramatic changes. The new tires are massive; they’ve widened from 13-inch to low-profile 18-inch rims. And it’s tough to choose – is the redesigned front or rear wing more eye-catching? The enormous front wing resembles a steely handlebar moustache. But it’s the raised rear wing that’s most visually transformative. Rejiggering the design pulls exhaust up instead of as did past versions, which spewed wake into the face of whomever was riding your tail.

A gamechanger is how many described the demographic wave of would-be millennial homebuyers who rushed to the suburbs and exurbs following the Covid 19 outbreak. A mid-January survey by Clever Real Estate found that 82% of the biggest age cohort in America had at least one significant regret about having made the plunge into homeownership. This compares to a Bankrate survey from June 2021 whose findings showed 64% of millennials regretted becoming homeowners. Call it ‘bidding war remorse’ as so many have infamously paid well over asking prices for fixer-uppers in less than desirous neighborhoods – a multifaceted blow to budgets as the mortgage payment and costs to repair and upkeep a home compete for top spot as the most burdensome.

It’s clear that essentials inflation has arrested the refurb surge, which stands to reason as food and utility inflation impair after-tax incomes regardless of where you live. Making matters worse, many former urbanites have been called back into the office. Between the cost of the (record high price) car payment and fast rising pump prices, that roundtrip trek to work, from what many consider to be the decidedly unhip hinterlands, is on the rise. This especially pours salt in the wounds of millennials, 40% of whom said their biggest regret was buying in a bad location, the highest-ranked regret. Tied at 30%, the second and third biggest regrets were bad neighbors and cost of upkeep. Just wait until the cost of replacing that HVAC collides with what’s not covered by car warranties – think tires and brake jobs, which will pile onto recent millennial buyers’ misery given 27% report the value of their home has already fallen.

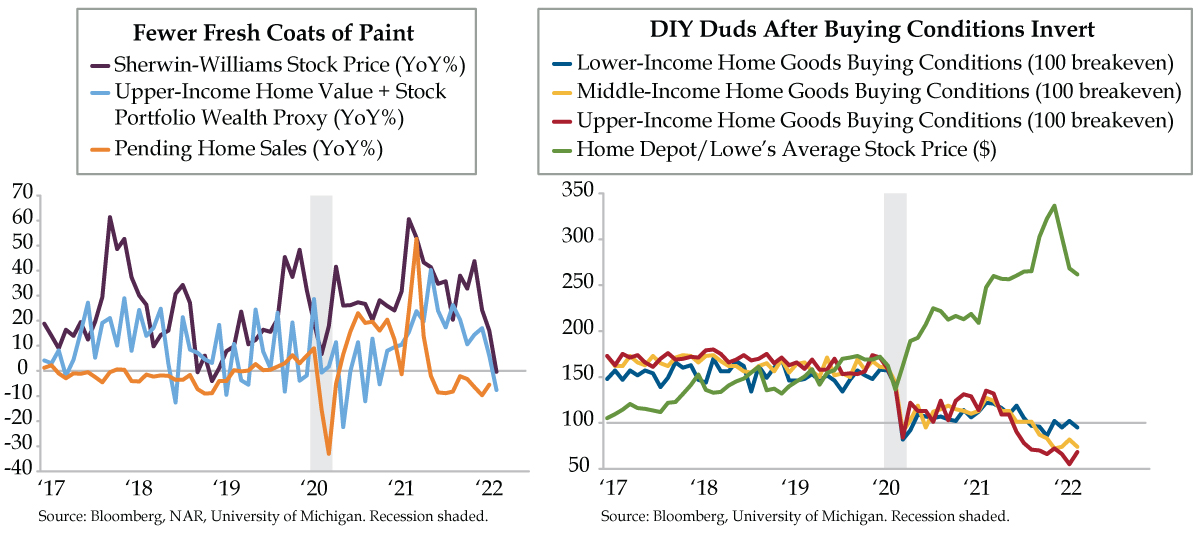

Of all the broad indicators, pending home sales (orange line) best reflect the state of the organic housing market. Consider that homes purchased by investors are never ‘pending’ as they’re inhaled before being listed by slick techie investors who make livings cold-calling existing homeowners. You clearly see the post-pandemic spike, which averaged 18% year-over-year growth in the year to May 2021; this has been followed by nine months averaging 6% declines in pending home sales – this is the baton handoff from those buying to live in a home to investors who want to rent them. It’s no coincidence that the stock of Sherwin Williams (purple line) peaked at the same time.

We would also note that souring views on housing are led by those in the middle- (yellow line) and upper-income (red line) terciles who, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, account for a combined 78.1% of spending on Owned Dwellings. With full disclaimer that we’re no stock pickers, it’s curious that the trend in the stocks of the big two home improvement retailers (green line) has been relatively resilient vis-à-vis the collapse in homebuying sentiment.

One thing is for certain – fence-sitters are not jumping en masse. On Friday, Richard Curtin of the University of Michigan (UMich) noted that, “Despite the dominance of rising prices, few consumers now favor buying-in-advance to avoid anticipated price increases, and few consumers favor borrowing-in-advance to avoid future interest rate hikes, despite the consensus view that prices and interest rates will continue to rise. This is quite unlike the last inflationary age when advance buying promptly gained favor at the first signs of inflation in the late 1960s.”

Some context: In the 1960s and 1970s, the U.S. household saving rate ran at about 12%; the mid-2000s housing bust, which was followed by the Federal Reserve’s post-2008 zero interest rate policy, halved that to roughly 6%. Moreover, the bulk of that cash stash resides in the hands of older Americans who already own homes, not the targeted millennial age group.

We sense further downside is in the making. Buried in the weeds of the UMich data are upper-income households’ takes on their homes and stock portfolios’ values (light blue line), a wealth proxy, or if you would prefer, wealth effect proxy. In March, this gauge fell into the red for the first time since late 2020. Given the S&P 500 is so close to its all-time-high, this is nearly as surprising a turn as Lewis Hamilton not qualifying for this past weekend’s latest F1 run. It would seem revolutionary design changes can indeed shake dynasties.