In 1983, Howard Schultz had an epiphany – an Italian epiphany. Then the Director of Marketing for Starbucks, Schultz traveled to Milan for a trade show. While walking the streets, he was taken by the local espresso bars that showed him how coffee was a daily social cornerstone, whose baristas knew their customers by name and brought people together between home and the workplace. Upon returning to the States, Schultz tried selling this idea to the original founders (Jerry Baldwin and Gordon Bowker). After a short, failed experiment, Schultz left the company and, in 1986, opened Il Giornale, his own Italian-themed coffee shop. Customers were greeted by a different sizing for their usual morning brew: ‘Small’ was ‘Short’ (8 oz), ‘Medium’ was ‘Tall’ (12 oz) and ‘Large’ was ‘Grande’ (16 oz, which literally means “large” in Italian). When Schultz bought Starbucks in 1987, these naming conventions came with him. As Americans demanded super-sized portions, the ‘Venti’ (20 oz) was introduced in the early 1990s. It became the new ‘Large’, pushing ‘Grande’ to ‘Medium’ and ‘Tall’ to ‘Small.’

These sizings don’t align well with the dismal science. Take the monthly jobs report from the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB), which precedes the full release earlier today. It is not a “Tall” business survey, it’s a small business survey. According to NFIB, “In January, 31% (seasonally adjusted) of small business owners reported job openings they could not fill in the current period, down 2 points from December. Unfilled job openings remain above the historical average of 24%. Twenty-five percent have openings for skilled workers (down 3 points), and 10% have openings for unskilled labor (unchanged).”

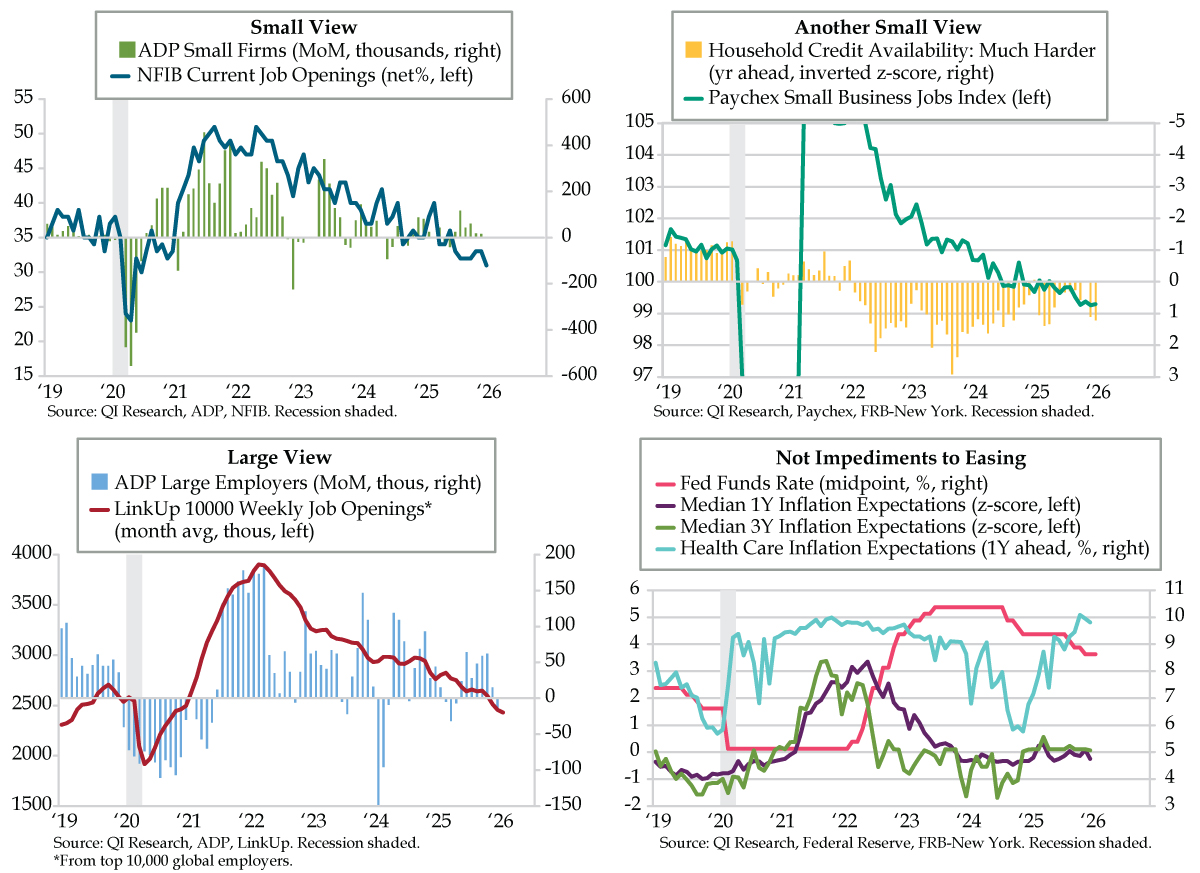

Last month broke new ground to the downside, reaching the lowest level since July 2020 (blue line). Outside of the pandemic, there was one other episode when NFIB job openings hit 31% “on the way down”: January 2001, two months before that recession started (not depicted). This small view on small business labor demand suggests that the ADP’s tally from Main Street’s proprietors could tip into the negative after posting no month-over-month (MoM) growth in January (green bars).

To be sure, ADP’s revised MoM path for small firm job growth has been uneven since late-2022; another round in the red appears due. Look no further than the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) small business job openings for a second measure of clairvoyance. Through December, this gauge plumbed to 2.91 million, the lowest since January 2021. On a six-month annualized basis, this measure of small firm employment guidance was anything but ‘Tall,’ sinking at a 22.9% rate, the weakest in 17 months.

Yet another small labor demand view comes from the Paychex Small Business Jobs Index. It provides a wide-ranging assessment of small business employment utilizing “approximately 350,000 Paychex clients.” Even better, it’s easy to interpret, scaled to 100, “which represents no year-over-year change in job growth among same store businesses,” according to Paychex. The January report extended the contractionary streak to nine consecutive months and 16 in the last 19 (teal line).

Going granular, only two of eight private industries Paychex tracks indicated figures above the 100-line: (recession-proof) Education and Health Services, at 100.57, and Financial Activities, at 100.11. The other six – Other Services (99.60), Professional & Business Services (99.17), Construction (99.07), Trade/Transportation/Utilities (98.99), Leisure & Hospitality (98.32) and Manufacturing (98.29) – all contracted. From a geographic perspective, just one of twenty metro areas tallied was in expansion – Philadelphia (100.39).

Little wonder the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) revealed households perceived the left tail of credit availability in the year ahead to have bulged significantly in the last couple of months. Normalizing the “much harder” to access credit response, December’s and January’s z-scores of 1.1 and 1.2 respectively (inverted yellow bars) indirectly flag worsening lending expectations through the eyes of consumers. With the labor recession deepening, bankers are signaling a tightening in lending standards.

At the opposite end of the business-size scale, after a relatively stable second half of 2025, LinkUp’s 10000 Weekly index has markedly deteriorated in January and February (red line). LinkUp’s index captures U.S. job openings from the top 10,000 global employers in its sample, i.e., a good read-through to large-firm employment prospects. To that end, ADP already reported a MoM decline of 18,000 for large employers in January, the worst since April 2025 (light blue bars). Because the reality in LinkUp data has yet to fully filter through the large company payrolls, additional job losses should be expected over the balance of 2026’s first quarter.

Monday’s SCE also revealed stability in short- and medium-run inflation expectations in January. Applying our favorite normalizer, the one-year rate of 3.09% and the three-year figure of 2.98% scaled to respective -0.3 and 0.1 z-scores (purple and lime lines). Inflation expectations remaining contained help the doves’ case and so does the rising expectation for health care inflation. Reports of higher employee premiums hitting paychecks in 2026 effectively raise benefit costs and pack the potential to lower take-home pay without a corresponding increase to employee compensation.

The easing in perceived health care inflation to 9.8% in January from November’s 10.1% is cold comfort, especially if you’re a worker who got a relatively lower inflation-adjusted bump in pay. From the “Tall” and “Venti” sides of the coin, job creation is getting squeezed. With inflation expectations contained and nondiscretionary health care costs expected to rise rapidly this year, FOMC Doves – led by Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller – should have ample evidence to make a strong case for easing in March despite rates traders only pricing for 19% odds of that happening.